How a red-neck Alabama sheriff made hard-hitting journalism possible

Once upon a time, actually covering the news often landed you in court. During the Civil Rights movement Southern government officials had a clever way to control the press. They’d sue them. If the New York Times covered how police set dogs on protesters, government officials would sue the New York Times claiming libel. When a network newscast showed video of police using fire hoses on Civil Rights marchers, local government officials filed libel suits.

While these nuisance law suits may not slow down big news agencies like NYT, the threat of lawsuits could and did influence how or whether news organizations would cover controversial issues. The threat of a lawsuit acted as a chilling effect for some organizations to cover the news. Then New York Times v Sullivan came along.

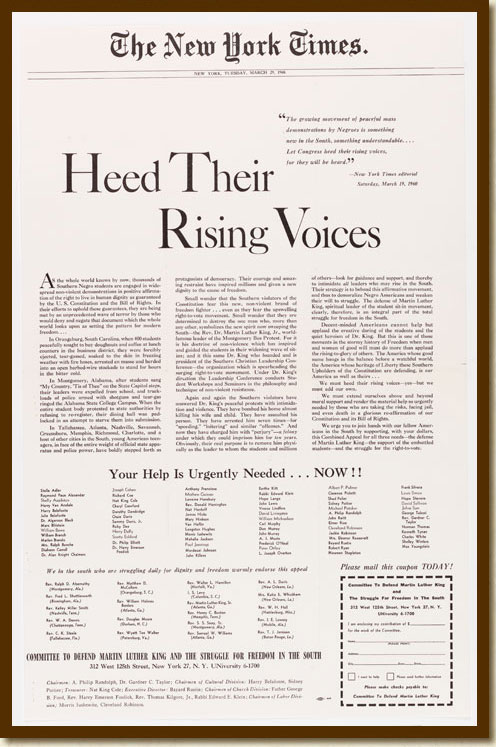

It started with an advertisement in support of Martin Luther King

In the 1960s Martin Luther King and other Civil Rights advocated for voting rights, the right to ride a bus or go to a restaurant or bathroom without being segregated. Many times MLK got arrested for fighting for these rights. While chilling in a jail cell, supporters created and bought ad space in the New York Times trying to raise money for MLK’s legal fund.

The Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South shared stories in the ad describing incidents where police took action against peaceful protestors. You can read the entire advertisement March 29, 1960 ad here. Here’s one of the stories.

“In Montgomery, Alabama, after students sang “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee” on the State Capitol steps, their leaders were expelled from school, and truck-loads of police armed with shotguns and tear-gas ringed the Alabama State College Campus.

When the entire student body protested to state authorities by refusing to re-register, their dining hall was pad-locked in an attempt to starve them into submission.”

The ad did have some factual errors.

- In one story, the ad said police set up a “ring” around campus. They didn’t.

- In one case, the protestors sang the National Anthem, not “My Country ‘Tis of Thee”

- Police did not padlock a dining hall, but they did turn away students who didn’t show their meal cards

The Sullivan Suit

L.B. Sullivan, the Police Commissioner in Montgomery, Alabama, and several others filed lawsuits against the New York Times.

Sullivan sued the NYT for $500,000 (that’s $4.9 million in today’s dollars) claiming false and defamatory statements.

Interesting facts

- Sullivan’s name isn’t in the ad, but he argued the police actions described in the ad reflected badly on his reputation.

- Only 35 copies of the “offending issue” circulated in his county

The Alabama trial court ruled in favor of Sullivan. The case went to the Alabama Supreme Court. The upheld the defamation award.

Then, the case landed in the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS). They ruled against Sullivan.

SCOTUS created two tests that make New York Times v Sullivan a landmark case: defining public officials and establishing “actual malice.”

A State cannot, under the First and Fourteenth Amendments, award damages to a public official for defamatory falsehood relating to his official conduct unless he proves “actual malice” — that the statement was made with knowledge of its falsity or with reckless disregard of whether it was true or false.

Let’s say every time the Ellensburg Record publishes an unflattering story about the Kittitas County Commissioners, the commissioners sue. How likely is the newspaper going to print stories about misspent dollars, embezzled money, or other shenanigan’s the commissioners are up to if they know they’ll be sued? That’s called the “chilling effect.” The threat of numerous lawsuits might stop or slow down the number of county commissioner stories the newspaper prints. In the meantime, the commissioners commit their illegal shenanigans without the public knowing.

New York Times v Sullivan gives journalists, like the Ellensburg Record, a chance to share information without a HUGE fear of legal retribution because they got a few minor facts wrong. NYT v Sullivan gives journalists room to cover and uncover what’s going on in government. SCOTUS said public officials must be scrutinized in order for the government to be accountable.

So, what does that mean? President Trump often threatened to sue the New York Times or the Washington Post or CNN or whatever news organization he didn’t like that week. He could say he could sue, and he could. The truth is he’d have to prove the news organization published the information “with malice.” How do you prove that? How do you prove a reporter didn’t check sources or showed reckless disregard for the truth?

Now, that doesn’t mean that the press can print anything they want. Let’s say someone walks into the Ellensburg Record newsroom and tells a reporter the commissioners stole money and plan to use it for a vacation in Cancun. If the newspaper printed that story without making an effort to verify the information, they would be showing a reckless disregard for the truth. They would be printing the info with “actual malice.”

If they interview five people who all say the commissioners are embezzling and write the story, they made a good faith effort to confirm facts before going to print. SCOTUS says if what they print, even if it’s false, was printed without “actual malice” the public official has no libel case.

Public official vs private citizen

So, who are public officials? Well, the folks who get elected to office. So, someone like Gov. Jay Inslee is a public official. But you don’t have to be elected to be considered a public official. When Heidi Behrends Cerniwey took the job of Ellensburg City Manager, she became a public official. So is CWU’s president Jim Wohlpart.

Basically, anyone who controls a budget or supervises government employees. So, a school bus driver wouldn’t be a public official, but the person who hires and fires drivers and decides what equipment to buy for the bus garage is a public official.

But it’s not always clear cut. As the advisor to Central News Watch I decide who gets paid and who doesn’t. Does that make me a public official? The answer is it depends on the nature of the story.

- When the story is about a Civil Service Commissioner who spent more time at the gaming tables than at the convention she’s out of town to attend, she’s a public official.

- The county coroner is a public official. But when another county hires her to do an autopsy, she’s no longer a public official.

- How about a story about the fire chief’s personal finance problems versus the city auditor with personal finance problems? In this case, the fire chief is a private citizen, but the city auditor is a public official. (Finance problems don’t directly impact the fire chief’s work versus the guy who’s supposed to keep track of the city’s money has trouble keeping track of his own.)

A New Twist: Public Figures

Since NYT v Sullivan, other cases have created another class of people… the public figure. SCOTUS defines public figures as people who “…occupy positions of such pervasive power and influence that they are deemed public figures for all purposes.”

But is it power or fame that determines if you are a public figure? I’d say Harry Styles, wh has two songs in the Top Ten this week, and Jennifer Lawrence, one of the highest paid actresses in Hollywood, are both public figures.

But what about Doug McMillon? Who is Doug? He’s the CEO of Walmart who controls the lives of over 2 million employees. What about the owner of Amazon and The Washington Post, Jeff Bezos? Is he a public figure?

Let’s say you’re Alec Baldwin and you’re pissed about the cover and headline of this week’s National Enquirer. Can you sue the National Enquirer? Sure. Will you win? Probably not. Public Figures have to show the National Enquirer showed reckless disregard and published the story without malice. Once again, how do you prove that. That’s why celebrities generally don’t file libel lawsuits. They may bring attention to the libel, but they won’t win the case.

Private Person

But what happens if the Ellensburg Record prints untruths about you or me? Well, they’d better get a lawyer. The “actual malice” test doesn’t apply to private citizens. If the newspaper prints that I spent 6 years in prison before coming to Central to teach, I’m going to get rich quick! I don’t have to show malice. I don’t have to show reckless disregard. All I have to do is prove I didn’t do time. BTW – I didn’t!

So, what does New York Times v Sullivan ultimately mean?

If you’re a public official or a public figure, you must prove actual malice if you want to win a libel suit. If you’re a private citizen, then all you have to prove is the information is false.

Where we get into gray ares is determining who is and who isn’t a public official. When does a government employee become a public official? And who is and is not a public figure?

New York Times v Sullivan gives journalists their Freedom of the Press rights to act as watch guards of the government, without the fear of being sued into bankruptcy.