by Terri Reddout

Has something like this ever happened to you?

Mandi walks to class one morning thinking what a great day it is. She sits down in the classroom and takes a sip of her perfectly flavored latte.

Mandi walks to class one morning thinking what a great day it is. She sits down in the classroom and takes a sip of her perfectly flavored latte.

As she pulls out her books, she mentally congratulates herself for taking the time to talk to the professor. After their conversation, Mandi got a much clearer idea what the assignment was about. So, instead of dreading writing the paper, she hammered it out in 30 minutes. Mandi felt so confident she uploaded it to Canvas a day before it was due.

Now she’s looking forward to spending the weekend with friends but remembers she needs to send her roommates a text to remind them she’ll be out of town.

That’s when Sam sits down next to her, slams his textbook on the table and says “Why are you mad at me?”

Mandi’s mood takes a sudden shift. She was happy. Sam attacked her and she doesn’t understand why. She was just sitting there having a great day and suddenly her buddy Sam comes along , accuses her of being mad and basically ruins what started out to be a great day.

Okay, let’s look at the same situation from Sam’s point of view

Sam walks in the door and tries to make eye contact with Mandi. Each day they have this thing where Mandi waves him to come in and sit down with her. He really looks forward to Mandi’s wave. It always cheers him up and makes him feel welcome. But today Mandi is ignoring him.

Sam walks in the door and tries to make eye contact with Mandi. Each day they have this thing where Mandi waves him to come in and sit down with her. He really looks forward to Mandi’s wave. It always cheers him up and makes him feel welcome. But today Mandi is ignoring him.

He knows Mandi is stressed out about the paper due at the end of the week and she seemed a little put off the other day when he mentioned he had already turned it in. Sam starts to sit down at the table but Mandi turns away while sipping her coffee. She continues to ignore him by grabbing her phone and texting.

Sam’s textbook accidentally falls out of his backpack, startling Mandi. That’s when Sam looks at Mandi and says “Why are you mad at me?”

Let’s replay this scenario with a twist

Mandi walk into the class feeling great. She grabs her phone to text her roommates before she forgets. Sam’s book startles her. When she looks at Sam he says, “Hey, you didn’t wave to me when I walked in the door. In fact, you didn’t look at me. You just took a sip of your coffee and started digging around for your phone. Are you upset with me because I got my paper finished early? Or are you stressed out about getting ready for your trip this weekend? What’s going on?”

How would you think Mandi reacted to Sam’s question this time? Better than when he point blank asked her “Why are you mad at me?”

In this scenario, Sam used a technique called a perception check. It’s a method of determining whether your perception is correct without putting the other person on defensive.

In this scenario, Sam used a technique called a perception check. It’s a method of determining whether your perception is correct without putting the other person on defensive.

It lets the other person know what it is you are reacting to that’s causing your perception. (Remember the selecting stimulus step of the Perception Process?) It allows you to determine if you are organizing the stimuli (Perception Process step 2) and perceiving the situation correctly (Perception Process step 3).

In many cases, it saves you from a situation where you end up with your foot in your mouth. (Imagine how Sam is going to feel when he finds out Mandi only got mad at him after he asked/yelled “Why are you mad at me?”)

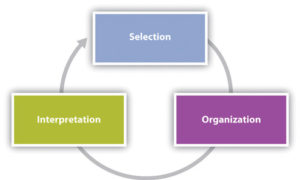

To understand how a perception check works, we need to review the perception process

As you may remember, the perception process helps us understand how we form our perceptions.

As you may remember, the perception process helps us understand how we form our perceptions.

- We select a stimulus. Something we hear, see, smell, taste or touch. We select a stimulus for many reasons based on how often it happens or its intensity.

- We organize that stimulus based on our experiences. How you organize a stimulus might be quite different from how I organize it.

- We interpret what the stimulus means and we react to it.

So, when I first moved into my downtown apartment I selected the noise coming up from the street in front of (what was then) Pizza Collin. Generally, sometime between 12:30 and 1:30 in the morning I’d hear people yelling about how much they f**king loved someone or hated someone. The intensity of the yelling woke me up. Based on my experiences waiting tables as a college student, I organized that yelling as a situation about to get out of control. I remember seeing drunks get over emotional and watched how the bartender and the cook would have to talk the drunk down. We even had to call the cops a couple of times. I interpreted the yelling in front of Pizza Collin as a fight about to start so I called 9-1-1.

Soon, my perception of what went on outside Pizza Collin in the wee hours of the morning changed. Now, if someone yells under my window, I wake up, think to myself it must be sometime between 12:30 and 1:30, then roll over and go back to sleep. It’s the same stimuli but, based on the experiences I gained living downtown, I now organize and interpret it differently. My perception has changed. What was true for me when I first moved into my apartment is no longer true for me today.

So, what is a perception check (and how does it relate to the perception process)?

The perception check recognizes the perception process. It lets the other person know what stimuli you are reacting to, how you are organizing and interpreting it.

It allows you to express yourself more clearly and decode messages more accurately. It reduces the chances of defensiveness while increasing mutual understanding.

Remember the Sam and Mani scenario above? Which one do you think has the best outcome? The perception check or the “Why are you mad at me?” scenario?

How a perception check works

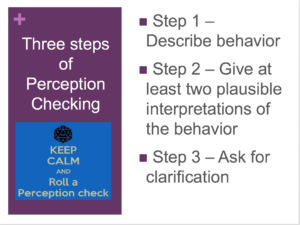

Just like the perception process there are three steps in a perception check.

Just like the perception process there are three steps in a perception check.

- Step 1: Describe behavior

- Step 2: Provide plausible explanations for that behavior

- Step 3: As for clarification

Let’s walk through it.

Describe behavior: This is where you let the other person know what stimuli you are responding to. In our classroom scenario, Sam describes the behavior (stimuli) he was responding to.

- “Hey, you didn’t wave to me when I walked in the door. In fact, you didn’t look at me. You just took a sip of your coffee and started digging around for your phone.”

What’s important here is that you describe the behavior and avoid judgemental language. It changes the tone and makes your statement more confrontational if you interpret the behavior.

Imagine if Sam had said, “You completely ignored me when I walked into the room.” That may be true from his point of view, but how do you think Mandi would respond to Sam’s comment? She’s just sitting there thinking how well things are going and how much she’s looking forward to the weekend, when Sam suddenly accuses her of ignoring him. Not good. Describe the behavior; don’t interpret the behavior. There’s a good chance you’ll be wrong.

Next, you provide at least two plausible explanation for the behavior.

In our scenario, Sam provides two explanations for what appears to be Mandi ignoring him.

- “Are you upset with me because I got my paper finished early? Or are you stressed out about getting ready for your trip this weekend?”

A couple of things. First, you need to include your perception in the explanation. Second, you need to communicate there could be possible other explanations for the behavior. It gives the other person another option for their behavior. Imagine if Sam had just asked if it’s because he had finished the paper first? How out of left field this might seem for Mandi. She’s finished writing the paper and is feeling good about it. Why is Sam rubbing it in her face that he finished first? By providing another option, Mandi sees there are different ways of interpreting her behavior.

Last, ask for clarification. Basically, it puts the ball in the other person’s court.

- “What’s going on?”

Asking for clarification can be something as simple as asking “What’s up?” It could be more complex like “I’m only asking because I’m concerned about you.” Or you could simply give them a non-verbal cue like a nudge or a look. The idea here is to communicate here’s what I’m thinking and I’d really like you to respond.

But Terri….

But Terri, these perception checks sound so awkward and unnatural. I just don’t talk that way.

Well, practice makes perfect. Like everything else, the more you use it the more natural it becomes. In fact, after I learned what a perception check was, I realized the man who taught me used it all the time.

When he asked questions during a faculty meeting, he asked in the form of a perception check. I soon realized the emails he sent me about overdue scripts were actually perception checks. He used perception checking so often, it became a normal part of his speech patterns.

I can’t say perception checking is completely natural for me now. But I do know it’s easier now than it was several years ago. I can also tell you I’ve avoided a lot of potentially embarrassing situations because I took a moment, composed my thoughts and did a perception check.

For example, there’s been so many times when I’ve walked up to a group in one of my classes and wanted to ask “Why aren’t you working on the assignment?”

There’s an equal number of times I saved myself from an embarrassing situation by perception checking the group. Often I’ll learn why a group member was talking about her camping trip is because was an example of a communication concept.

Imagine how the mood of the conversation and my relationship with the students would change if I had just marched up and and asked why they were talking about camping and not communication.

And even if the group was off-task, I’ve still communicate a message that I think they’re goofing off. They may even fib and say the camping trip had something to do with a communication concept I asked them to discuss. Now, thanks to the perception check, they know that I know they are screwing around and need to get back on topic.

But Terri, isn’t it just easier to tell the other person what my perception is?

Sure. Let’s try it.

“Yeah, you! It’s clear you don’t know any of the perception check warnings. Why is that?”

How do you feel? Confused? Pissed? Hurt?

Often, stating your perception puts the other person on the defensive. If you are on the defensive, that’s a communication “noise” gets in the way of us communicating effectively. It may be easier and quicker to state your perception, but you may not like the results.

Let me try it again.

“Yeah, you! When I asked what are some of the perception check warnings I wrote about in my blog, you didn’t answer right away. Is it because you were trying to remember what you wrote down in your notes? Or is it because you didn’t read my blog? I only ask because you really need to know this stuff before you attempt the two perception check assignments.”

How do you feel this time? Do you understand what you did (stimuli) that made me come to my perception? Do you have an idea how I organized your non-response? Did I communicate my perception (interpretation) that I didn’t think you finished reading this blog? Do you see I’m giving you some benefit of the doubt? Do you feel I really want to hear your side of the story?

That’s the beauty of a perception check. It gets your point of view across. It gives the other person an idea of what stimuli you are reacting to. It shows the other person you recognize there may be other reasons for his or her behavior. It invites conversation without putting the other person on the defensive. A perception check is assertive, without “getting up in your grill.”

BTW- I know now why you didn’t answer when I asked about the perception check warnings. It’s not because you didn’t read the blog. It’s because the warnings about perception checking are in the second part of this blog. So, now, go read Perception checking: One powerful tool.