At Purdue Polytechnic Institute an engineering professor wanted his students to become better presenters. . He wanted them to get better at pitching the project. He wanted his students to have the tools to persuade future clients to buy into their proposed projects. So, the engineering professor wandered over to the Communications Department and knocked on the door of Dr. Alan H. Monroe.

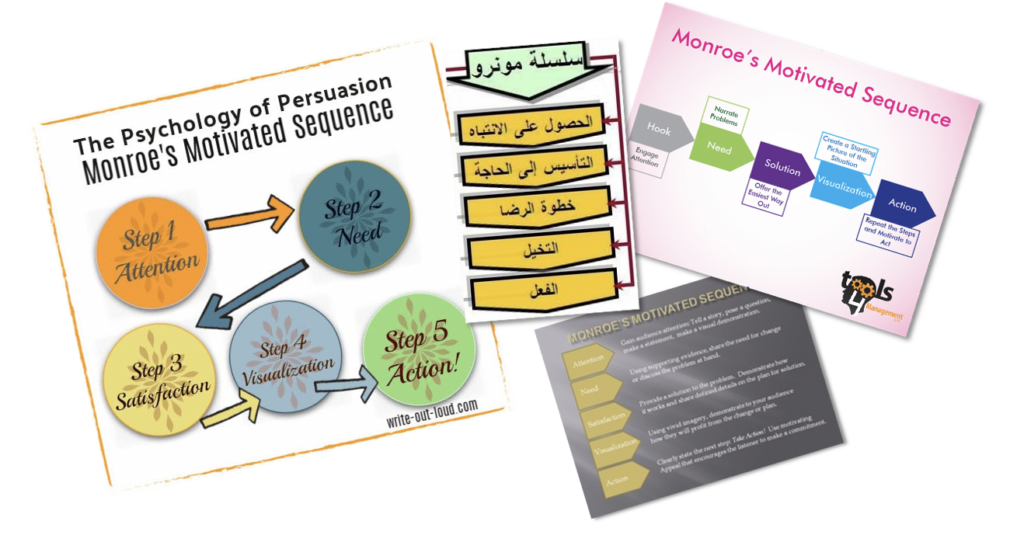

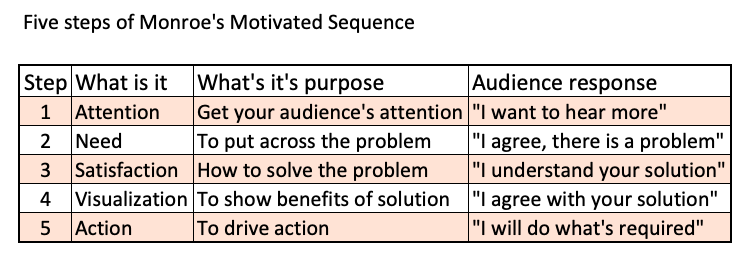

Monroe took on the challenge and developed Monroe’s Motivated Sequence. It’s basically a template where you plug in the right information and you end up designing a persuasive speech or argument.

The thing is, this happened back in the 1930s. Yet today at Purdue, all students who take freshman communication classes learn Monroe’s Motivated Sequence. Today, Purdue professors expect seniors to use MMS when presenting their senior projects.

“Students are expected to use Monroe’s Motivated Sequence heavily for their final project according to new curriculum in the Purdue Polytechnic Institute.”

Yes, there are other persuasive techniques but I like how Monroe maps out his persuasive method. Also, a majority of the students in COM 345 come from electrical, engineering and safety related majors. I thought if it works for Purdue engineers, it’s good enough for CWU’s engineers!

A man of mystery

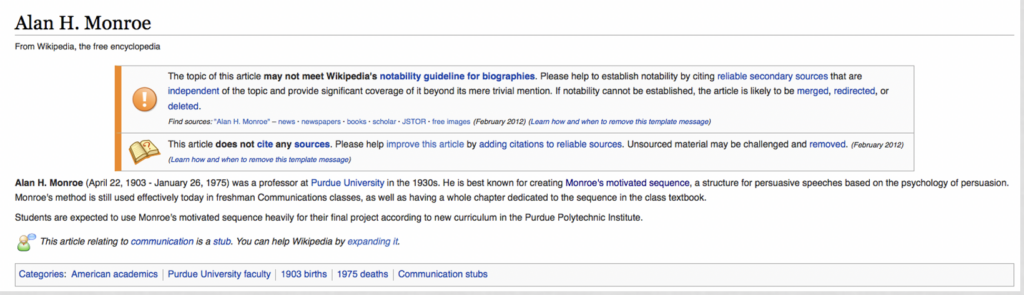

Take a look at a speech textbook. You’ll probably find Monroe’s name in there somewhere. Even though he died in 1975 he’s still listed as one of the authors of Principles of Public Speaking textbook. Purdue offers scholarships in his name. Mention Monroe’s Motivated Sequence to anyone who teaches rhetoric and they’ll immediately know what you’re talking about.

MMS is used by corporations, and educational institutions at the high school, university and advanced degree level. Professional communication experts use it. I even found a graphic of Monroe’s Motivated Sequence written in foreign languages.

But who was Monroe and what was the rationale behind each step of his sequence? I asked my rhetorical friends. They knew the five steps of MMS, but they didn’t know the thought-process behind those steps. I turned a CWU research librarian loose on the question. She came back with three research papers Monroe had written about topics other than MMS. I even contacted Purdue. They pointed me in the direction of the same three research papers. After all my research, the most information I could find in one place on the elusive Dr. Monroe was a Wikipedia page!

So, I can’t tell you why it works. I can tell you for years I’ve had students use MMS for their persuasive speech. I know it involves some psychiatry and tapping into people’s needs. I can also tell you it works!

5 steps with the goal to persuade

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence is a series of steps that build on each other to motivate people to do what you want them to do. Just because you use MMS doesn’t 100% guarantee you’ll persuade someone but it does up your chances.

Step 1: Attention

So the first thing you need to do is grab your audience’s attention. But how? Well, you could make a startling statement. You could arouse curiosity or suspense. You could use a quotation, an anecdote or dramatic story. You could pose a question. You could use visual aids.

So you could start a speech about microbs with the line “Space aliens live among us…”

If you heard “I’m going to tell you how you can pay off your student loans in half the time” wouldn’t you pay attention?

Once a student started his speech with the line “Do you believe in ghosts?”

I started a speech about water pollution caused by dairies by pouring milk into a glass of water while saying “Every day this wholesome product pollutes something we must have to survive… water.”

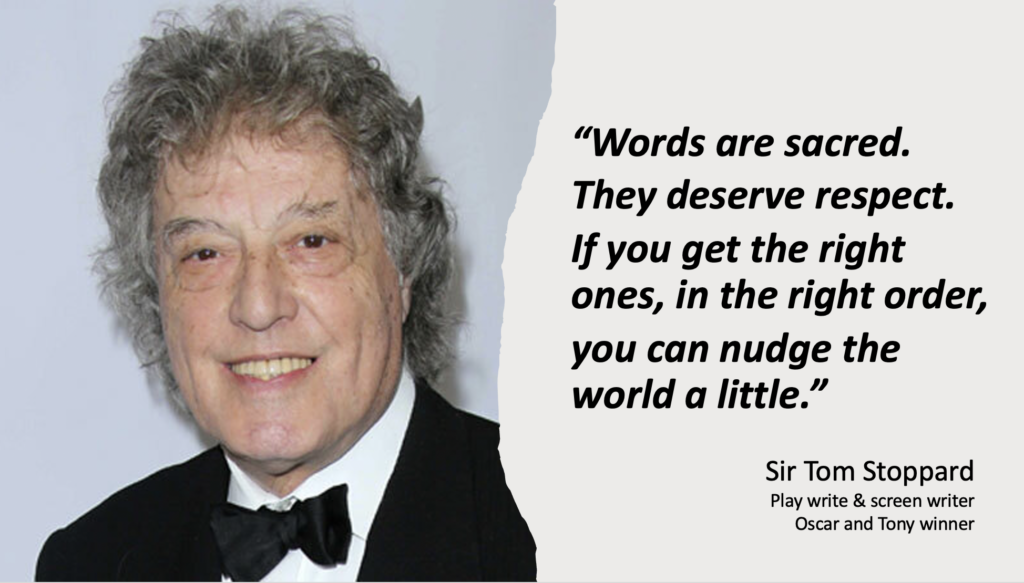

A speech about improving writing skills might start with this PowerPoint slide.

The speaker might say…

“Words are sacred. They deserve respect. If you get the right ones, in the right order, you can nudge the world a little.”

The man who wrote these words knows what he’s talking about. Tom Stoppard has an Oscar, a Tony and multiple other awards for his writing.

Words are sacred. They do deserve respect. They do change the world. But we as a culture and society are losing our ability to write and write well.“

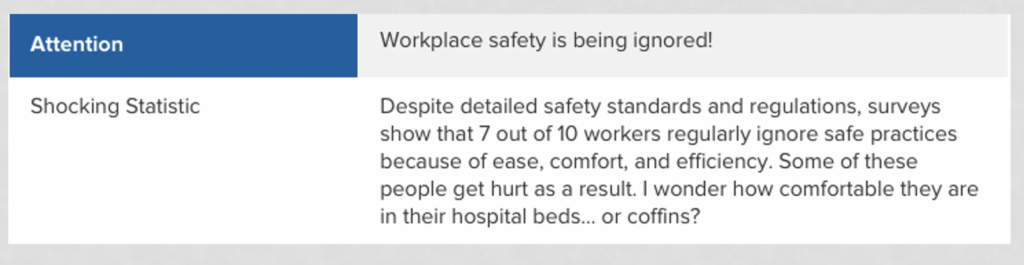

Attention example

I pulled this example from the Mind Tools web site. They consult big corporations on professional and personal development. I like it because the focus of the example is workplace safety. The speech starts with a shocking statistic and then puts that statistic into more personal, relatable terms.

What’s in it for me? (aka WIIFM)

I once had a young woman ask for some time at the beginning of a class. She needed on-line votes to make it into the Miss Washington pageant. She explained the situation and asked her classmates to please vote for her. Then a young man raised his hand and asked, “What’s in it for me?” Now, I have a sneaking suspicion the young man wanted wanted a date with the beauty queen but his question does point out a problem with persuasion. The young woman explained her problem but she didn’t give her audience a reason to take the time to go on-line and vote (other than just being a nice person).

The bottom line is, you need to give your audience a reason to stick around and pay attention. Think of it from their point of view. Your audience sits there and asks themselves, “What’s in it for me?” How will what you say make their lives easier? How can the project you’re pitching save them money? Will your audience leave your speech with some tools to help them solve a problem? Figure out the WIIFM and you’ll have the material you need to start your speech.

Step 2: Establish a need (aka establish there’s a problem or opportunity)

Now that you’ve got their attention, you need to let them know there’s a problem or opportunity. You need to illustrate how it affects your audience. You need to make them feel a need for change.

This is not a “we need to…” statement. That happens in step 3. How do you establish there’s a problem or opportunity? In MMS, it’s a four-part strategy.

- #1: Make a simple, concise statement or description of the need. Make them aware of the problem or opportunity.

- #2: Provide examples illustrating the need. The example should provide pathos or an emotional reaction.

- #3: Offer statistical data or expert testimony. The example should provide the logos or logic.

- #4: Show them the impact on their lives. Prime your audience to hear your recommendations.

Let’s say your speech is about parking problems on Central’s campus. You might establish there’s a problem by saying this:

“Central has a parking problem. For every parking space on campus there are 15 students trying to park there. (Statement of problem)

Josh Anderson knows what that’s like. He drives to campus straight from his job that pays for his tuition and living expenses. Even when he arrives 20 minutes before class, he spends 40 minutes cruising the parking lots looking for a parking space to open up. By the time he runs to class he’s missed half his class. (Pathos or emotional example.)

And he’s not alone. In a survey of 500 CWU students on Ellensburg’s campus, over 74 percent said they were late for class two or more times because they couldn’t find a parking space. (Logos or logical example.)

It’s not just irritating. Being late means students don’t get all they paid for from their classes. And in the case of Josh Anderson, his grade dropped one letter grade because he violated the professor’s late policy so many times. (Impact on lives.)

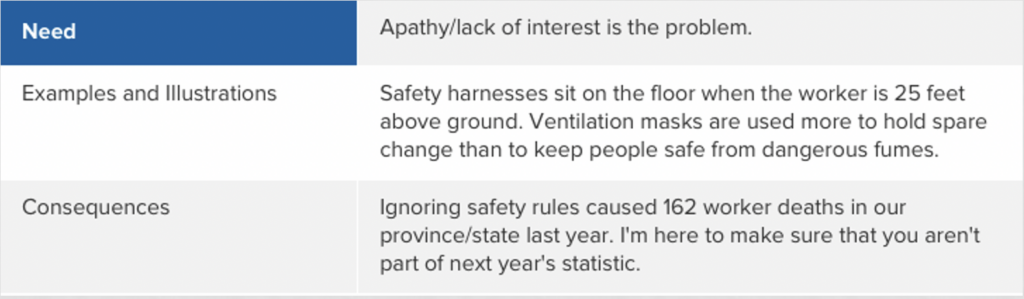

Need step example

In this example they state the problem clearly without any frills or details.

They provide an emotional illustration of safety equipment not being used properly. It paints a picture in the audiences’ mind.

The example uses statistics so the audience isn’t just relying on emotion to make a decision.

Then the example shows how the audience is impacted and primes them for hearing the solution by indicating that the audience shouldn’t become a statistic.

Step 3: Satisfy the need (aka offer a solution)

Now that your audience knows there’s a problem or opportunity that impacts them, you need to show them you have the solution. You need to clearly present your plan and then demonstrate how it will work. Once again, in MMS that’s a four-part strategy.

- #1: Start with a “should” statement. “We should donate blood…”, “We should allow concealed weapons on campus…”, We should raise the vaccination rate in Kittitas County to 75 percent…” , “We should petition campus administration to demand they double the salary of our professor, Terri Reddout,” (I wish Word Press would allow me to put a smiley face emoji here!). Let’s continue our parking garage scenario with “We should build a four-story parking garage near the SURC to ease campus parking problems.”

- #2: Outline your solution. Present the basic elements of your “plan.” Provide details. The more specific, the better. Don’t just say we need to fix a problem. Show them how to fix the problem. “This parking garage will add 600 parking spaces to campus. We’ll build it near the SURC because there is space and it’s the center of campus. We’ll use a combination of bonds and grant money to fund the project. The project will take a year and half to complete.”

- #3: Support your solution. Provide evidence or reasoning to convincingly prove your plan meets the needs and solves the problem. Provide facts, stats, or expert testimony to support the viability of your plan. Use charts and graphs, audio or video. Provide a demonstration. “We conducted survey of CWU students on the Ellensburg campus. The results show nearly 80 percent approve of the idea of a parking garage. When asked how they would feel about the construction going on in the middle of campus, one student wrote, ‘I’ve lived through the construction of several buildings on campus. I’m willing to walk a few extra steps so I that one day I won’t show up 30 minutes late for class because I had to cruise the parking lot looking for a place to park.’ The University of Connecticut is one of ten universities we studied. They built a parking garage on their campus four years ago. They project the parking fees will completely pay for the project in four more years.”

- #4: Overcome objections. I believe this is the most brilliant element of the sequence. It addresses all the “Yeah, but what about…” obstacles your audience works up in their minds. You identify what the major objections to the plan might be and then address them before anyone has time to say “Yeah, but what about…” “Yes, the construction will take away 150 desperately needed parking spaces away for one academic year. But we can build a temporary parking lot in this field along 18th Street that will provide 200 parking spaces. We’ll work with Central Transit to have a dedicated bus to run from 18th Street in a loop around campus to drop off students. Yes, it will cost a lot of money but we’ve looked at other campuses where they build parking garages and most pay for the garage construction within ten years. We project the CWU parking garage will pay for itself within eight years.”

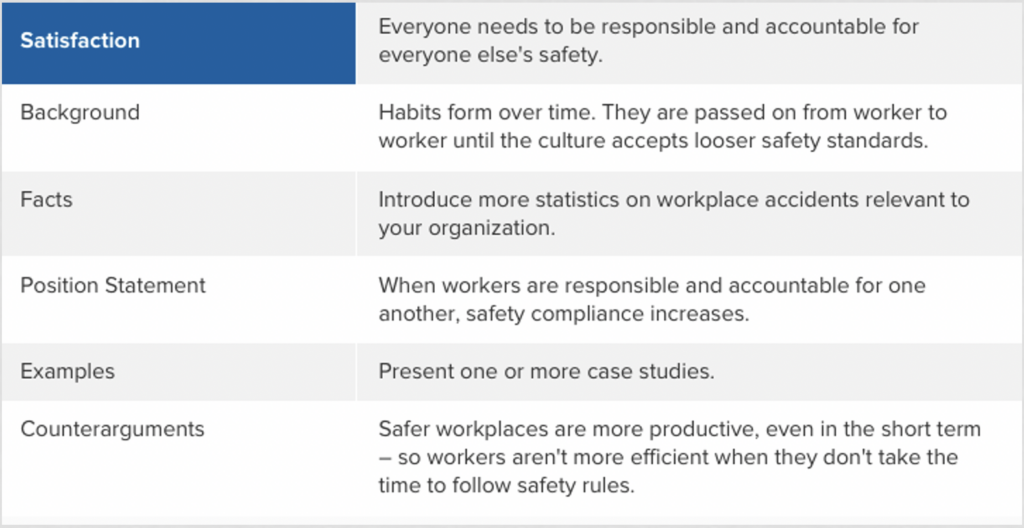

Satisfy the need example

The solution is stated simply… we need to set up an environment where everyone is responsible for everyone’s safety. The background section of this example seems a little weak to me. A plan for how to build a safety environment needs to be spelled out more. (I’m sure the safety majors in this class might have some ideas.) The facts section would be filled with facts, stats, and/or expert testimony that shows the logical reasons for taking this steps. The case studies would also provide examples that back up the plan. The “Yeah, but what about…” question of how much is this going to cost is addressed with in the examples counterargument.

Time for a safety/coffee break

So far we’ve examined the first three steps of Monroe’s Motivated Sequence. You should understand the rationale behind the steps and what the examples for each step might look like. It’s time for you to complete the MMS 1 assignment. We’ll tackle the last two steps in the next blog.